Switching to Beancount

I’ve been tracking my personal finances since 2005. What started as a exercise in wondering “where am I spending my money?”1 has evolved into something that has helped me quickly (well, maybe not that quickly) understand more about my personal finances over the years. I’ve hopped from tool to tool, always searching for something which balances flexibility, power and ease of use. I’ve adopted, used and then got fed up with apps like Moneydance, YNAB, convoluted spreadsheets, and most recently, a long stint with GnuCash. But now, I’ve found a new shiny thing: Beancount.

Some context

Before I explain what Beancount is, a brief mention about the broader concept to which it belongs: Plain Text Accounting. This is a method of managing finances using common or garden plain text files. It’s a magnificently simple yet powerful approach that matches my love of all things text-based. If you’re curious to learn more, the Plain Text Accounting website is a superb primer.

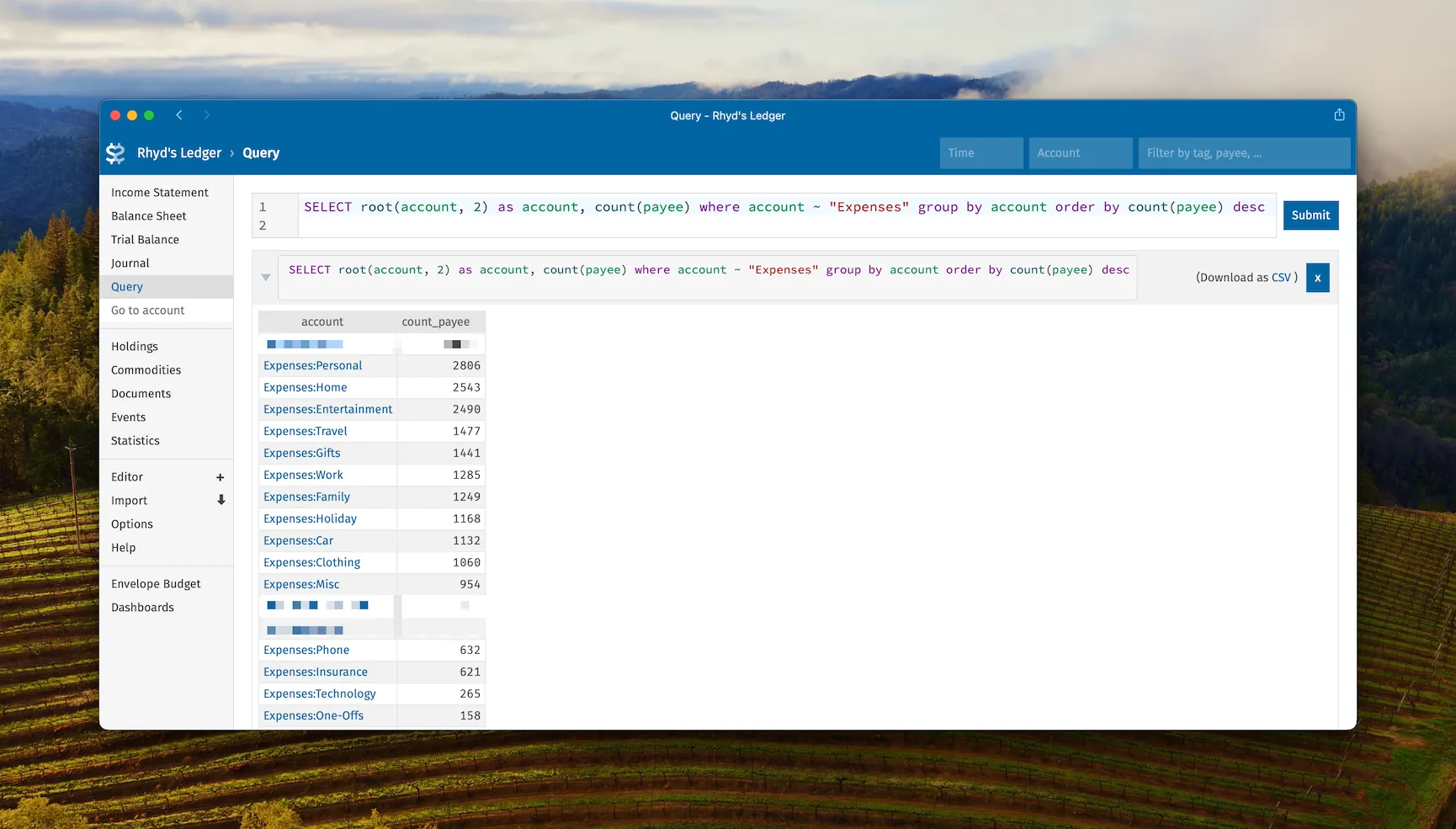

Beancount is one implementation of Plain Text Accounting. It’s a command-line accounting system that allows you to define financial transactions in a simple text format. What sets Beancount apart is its flexibility and its ability to generate reports and provide a web interface via a cracking tool called Fava. Fava is to Beancount what a graphical interface is to a command-line tool. It provides a web-based UI for your Beancount data, allowing you to visualize your finances, run queries and generate reports with ease.

Making the switch

I tried switching to Beancount before but got lost trying to work out how to migrate the near 20 years of data held within GnuCash’s database. The script I had didn’t work and so I parked it. However, this year I found someone else had cracked the problem which made migration relatively painless: enter gnucash-to-beancount.

After running my GnuCash data through this tool, I was left with a set of Beancount files. However, as with any automated conversion, there was some cleanup to do. I wrote some Python scripts to tidy up the generated files and rewrite the account structure to better suit my needs.

Useful Tools and Plugins

One of the things I love about Beancount is the ecosystem of tools and plugins that have grown around it. Here are some that I’ve found particularly useful:

- beanhub format: helps maintain a consistent format across your Beancount files.

- bean-add: a nifty tool for adding new transactions to your Beancount files via command-line.

- autobean.sorted: warns you if your transactions are not sorted by date

- beancount.plugins.noduplicates: warns if you have any duplicate entries

- beancount.plugins.nounused: flags any unused accounts

- beancount_reds_plugins.rename_accounts: provides a handy way of renaming accounts after processing (e.g. moving Tax related Expense accounts into the Income accounts tree).

- fix_payee_narration: this helps clean up payee and narration fields

My Current Setup

After much tweaking, customisation (and some gnashing of teeth after a bulk rename operation went very wrong), here’s how my Beancount setup looks today:

beancount/

├── personal.beancount

├── accounts/

│ ├── open-accounts.beancount

│ └── close-accounts.beancount

├── config/

│ ├── payee-rename.json

│ └── categoriser.json

├── importers/

│ ├── bank/

│ └── (importer python files)

│ └── credit-card/

│ └── (importer python files)

├── ledger/

│ ├── bank1.beancount

│ ├── bank2.beancount

│ ├── credit-card.beancount

│ └── historic/

│ └── yyyy-transactions.beancount

├── plugins/

│ └── fix_payee_narration.py

├── justfile

├── bank1.import

├── bank2.import

└── credit-card.importThe personal.beancount file is my main file that includes all other files. The accounts directory contains files for opening and closing accounts. The ledger directory holds my transaction files, with a subdirectory for historic transactions.

I use a justfile to define common actions. For example, I can run just format to format all my Beancount files, or just "bank-name" to import transactions from a specific bank account.

My Fava configuration includes some options to customize the interface:

"auto-reload" "true"— reloads the view when an underlying beancount file changes"invert-income-liabilities-equity" "true"— by default, income values in Fava are shown as negative values which messes with my head so this inverts the default"show-accounts-with-zero-balance" "false"— hides any account with a 0 value, aids readability"show-accounts-with-zero-transactions" "false"— ditto

I’m still experimenting with custom dashboards in Fava.

Importing Transactions

One of the biggest improvements in my workflow has been the ease of importing transactions. I’ve written 2 custom importers, one for my credit card provider and one for my UK bank. These importers use the smart_importer library along with a custom payee renamer and categoriser hooks to rename transactions, assign the correct account and check for duplicates before importing.

This process is significantly smoother than the manual entry or clunky import process I had to deal with in GnuCash.

Conclusion

Switching to Beancount has been a game-changer for me. The flexibility of plain text files, the power of Beancount’s double-entry accounting system and the visualizations provided by Fava have taken my financial tracking to a new level.

There was a slight learning curve to get my head around how to make waves hands in the air all of this make sense but it was a fun challenge. My system is more flexible, more powerful and — as an unexpected benefit — simpler than what I had before.

If you’re a fellow financial tracking enthusiast, especially one with a penchant for text-based tools, I highly recommend giving Beancount a try. It might just be the tool you’ve been looking for all along.

Header photo by Ben Wicks on UnsplashFootnotes

-

Or, the more realistic question of “aargh, why does my bank balance look so abject 😱?” ↩